From Silent Screens to Singing Stars: How Singin’ in the Rain Reinvents Two Eras

- Sofia Prieto Black

- Jan 5

- 10 min read

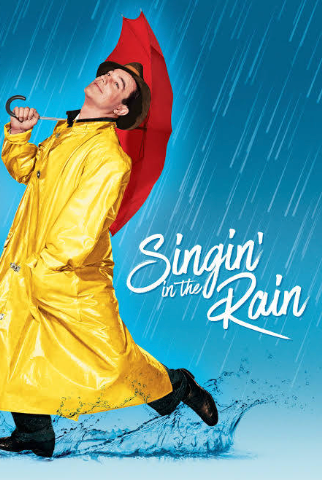

The year 1952 symbolized a monumental time in the U.S.’s grand tapestry of cultural and cinematic history. Only seven years after the global destruction and devastation created by the occurrence of World War II, Singin’ in the Rain emerged as a vibrant, joyous, and lighthearted musical that presented the technological challenges of the 1920s while simultaneously working to celebrate the golden age of Hollywood. Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen’s meticulous use of mise-en-scène--from carefully crafted set designs (that deliberately expose their fabricated nature) to perfected choreographed performances and innovative sound integration--creates a meta-cinematic experience that transcends mere entertainment; it explores the profound technological evolution of film while making audiences aware of the fact they are watching a movie within a movie. The cinema serves as a critical examination of film production’s sonic transformation, dramatizing the journey from the early, awkward implementation of sound in the 1920s--where microphone challenges and acoustic interference plagued productions--to the seamless and sophisticated sound design of the 1950s. Through its self-referential narrative and spectacular musical sequences, Singin’ in the Rain not only chronicles the technical progress toward the realization of elaborate full-scale productions, due to the technology available in the 1950s within Hollywood, but also reflects on how innovation at the time, permanently reshaped artistic expression, revealing and making an homage to how the initial limitations of sound recording became the very strength of cinematic storytelling.

The 1920s Transition to Sound Cinema

The era of silent films began in the nineteenth century, a time filled with some of the industry’s most remarkable cinematic masterpieces. As cinema continued to grow, performers mastered their extraordinary ability to solely communicate feelings to audiences through exaggerated physical performances, intricate facial expressions, and elaborate gestures. These silent films relied heavily on minimal but disruptive subtitles and dialogue slides that moved the narrative forward, helping to convey information to the audience that might have been difficult to express purely through visuals. Furthermore, anticipating the potential monotony of silent films, theaters regularly employed live bands to create a rich sonic environment, ensuring that screenings like “The Royal Rascal” were never truly silent, but instead vibrant and immersive performances for its audience. The early film production was remarkably efficient as the cinematographer could work without the complications of sound restrictions--directors would freely voice their notes and artistic directions to the actors as they performed live for the camera, and other miscellaneous set noises were inconsequential as long as the moving picture within the camera’s frame remained uninterrupted.

When the 1920s rolled around, however, things began to change. The revolutionary transition to “talking pictures” or “talkies” started, with filmmakers beginning to sync music scores to the movement of lips and Hollywood seeing the implementation of long and complex exchanges of dialogue between characters. This initial shift began disrupting and drastically altering the film industry’s artistic and technological foundations of reality. The transformation was driven by the audience’s desire to simultaneously see and hear what was on screen, wanting to become fully consumed by the performances. As engineers, scientists, and filmmakers began to recognize that silent films had inherent limitations in that the subtitles and dialogue slides consistently took away from and interrupted the narratives, this transition began to accelerate. This change reflected the rise in panic within production companies when something new became the public’s obsession. It showed the general filmmaker’s struggle of competing with other creatives in the industry to remain relevant while keeping up with the learning curve of using this new technology.

The technological transformation demanded radical changes to the actual filmmaking process--large and impractically heavy microphones, sound-insulated camera cabins with glass windows, and strict but necessary “Quiet While Recording” protocols. These changes began to dramatically reduce film production’s productivity. Yet still, early sound recording technologies were crude and limited, with microphones that were non-directional and incredibly sensitive.

Microphone placement was a constant challenge--early attempts included placing microphones on actors’ bodies or hiding them in nearby plants, often with disastrous results. These microphones captured every unwanted sound--from the rustling of props such as Lina Lamont’s pearls, mistaken for a thunderstorm outside, the beating of her heart when the mic is placed within her dress, or the disproportionately loud thud of her fan when she lightly strikes Don Lockwood in the premiere of “The Duelling Cavalier”--making film production all the more difficult. The new technology used for microphone setup also required that actors perform in much more subtle and rigid ways--speaking in the specific direction of the mic, at all times, to ensure their voices were captured clearly. This resulted in the abandonment of the broad, exaggerated gestures that had defined silent film performances for decades in the past and caused frustration within actors. These challenges were specifically seen when Lamont snaps back at the director as she’s told to speak into the hidden microphone saying, “‘Well, I can’t make love to a bush!’”

This technological shift, however, presented more than just a technical challenge--it symbolized a complete reimagining of cinematic storytelling and performance as a whole. As illustrated in this scene, this massive change created immense hurdles for actors who were only qualified to perform in silent cinema. Those who had carefully honed their skill set and techniques now faced the threat of their careers possibly ending. The industry was now forced to completely rethink how performers were selected, trained, and presented to the public--beautiful looks, baseline acting skills, and charisma no longer seemed to suffice as a reason to land once-qualified actors these new roles. Many of these stars struggled to adapt to the medium that no longer prioritized physical expression and instead heavily depended on dialogue and a more naturalistic performance. Lockwood, with his background in singing and dancing, however, acclimated relatively easily while leaving Lamont and several other actors of the time to struggle dramatically. Her high-pitched voice and inability to modulate her performance and gestures to accommodate the technicalities of sound technology became a comedic focal point that also highlighted the very real challenges faced by many silent film creatives.

Filmmakers created unique and innovative audio recording techniques to navigate the limitations of early sound technology that went around recording it on the spot. Some of these included pre-recording (where sound was recorded in advance and played back during shooting to guide actors’ lip-syncing) and post-dubbing (the process of adding appropriate sound and dialogue to scenes that had already been shot). Sound synchronization, however, presented another significant hurdle. Preview screenings of early sound films were often comedic disasters, with dialogue coming out of sync, voices sounding unnatural, and ambient noises overwhelming the intended dialogue and audiences. The first attempts at converting silent films to sound often resulted in awkward, nearly unwatchable productions as seen through the showing of “The Duelling Cavalier,” where the sound is so poorly managed that audience members mockingly call it “the worst picture ever made.”

In all, the film does a particularly splendid job of emphasizing the significance of the transition to sound through its dramatic emphasis on the proper use of a microphone. In their first important exchange in dialogue within their newest film “The Duelling Cavalier”, the camera frame specifically centers around the large circular audio tool, showcasing the impracticality of the microphone to Singin’ in the Rain’s viewers. The film also puts a large emphasis on the technology in having three consecutive scenes that are practically all the same. Each time, the director of “The Duelling Cavalier” explains to Lamont where the microphone is placed (having shifted locations several times to facilitate the capturing of the sound of her voice); in which specific direction she should speak as the camera is rolling; and how the sound will run from the metal disk, through the wire, to the box, where “a man records it in a big record in wax”. By presenting nearly identical scenes with slight variations, the directors create a humorous representation of the challenges actors faced during sound recording’s advent, underscoring the trial-and-error nature of technological innovation. Moreover, this deliberate repetition is a masterful comedic device that does more than simply generate laughs; it provides a self-reflective critique of the film industry and its stakeholders’ difficulty with this technological transition.

Depicted nostalgically and comically throughout the film, audiences can discern that this change symbolized a pivotal moment in cinematic history, revealing the frailty of Hollywood’s meticulously crafted star personas while celebrating the resilience and creativity of early actors and filmmakers.

The 1950s: The Product of Perfecting Sound

The technological advancements in sound recording and the growing comfortability of its related technologies in the decades of cinema leading up to the 1950s, paved the way for large-scale musically sophisticated films like “Singin’ in the Rain,” which represented a pinnacle of Hollywood’s mastery over sound integration in filmmaking. In the iconic rain dance sequence, Lockwood’s character navigates a deliberately dark and gloomy urban landscape, with occasional bursts of color--a red mailbox and vibrant shop windows--symbolizing joy amidst a non traditionally happy context (being soaking wet in the cold rain in the middle of the night). He maintains a wonder about the world making it almost extremely obvious to the viewer this is a fabricated reality. Gene Kelly’s performance creates a captivating audio-visual symphony, with each splash turning into a percussion instrument and every droplet into a musical note. Water, movement, and music all beautifully blend together to create a single artistic statement--one that is a testament to the technological advancements that enable this quality of work.

The pitter-patter of raindrops establishes a soft, constant background rhythm--a delicate percussive foundation upon which his performance builds. His tap shoes become instruments, creating a dialogic relationship with the falling water and constructing subtle splashes that match the initial musical tempo. Each step is carefully calculated, not just a movement but a sonic deliberation. With each step, water erupts in carefully controlled arcs, the droplets catching meticulously designed backlighting that makes every liquid movement visible and vibrant--such that wouldn’t appear in everyday life or even a regular, not as perfectly filmed setting. Backlight, key light, and fill light are utilized, positioned around the raindrops, to turn each one into a prism that refracts light in ways that give the camera a remarkably clear view of the water. Thus, the technological achievement of making rain visible to the camera is in itself an example of cinematic innovation.

Kelly’s motions get bigger as the musical score rises symphonically. What started out as faint splashes turn into dramatic puddle kicks and large, spectacular water eruptions. He moves from cautious steps to full leaps, each landing producing enormous water explosions that exactly match the intensity of the music--smaller ripples go with gentler melodic passages, while larger splashes match crescendos. The water becomes an extension of Kelly’s body and voice--no longer just a backdrop, but an active participant in the performance, melting into the beautiful tune of the song. It’s a total fusion of environmental sound, choreographed movement, and musical composition, all eliciting the corresponding emotions. The police officer’s arrival is the scene’s most brilliant moment. The music abruptly ends, leaving only the steady sounds of the rain. This sudden change turns into a meta-commentary on sound design in general, showing how audio can expertly produce suspense, mood, and story development.

Importantly, however, the scene does not explicitly try to hide how truly fabricated it is. In order to allow spectators to be amazed by the technological skill and level of production the studio was able to achieve in producing such a cinematic moment, they made the set appear entirely flawless--from the way the rain falls and puddles collect as well as its consistent pressure and appearance on screen to the fact that Lockwood remains perfectly lit that late at night during the entire duration of a complex choreographed dance in a thunderstorm; clearly a true signifier of movie magic! Hollywood creates this dream-like circumstance to fully immerse its viewers in a world so different from any possible reality--one where any life obstacle can be overcome through meticulous song and dance. It’s thanks to the extraordinary technological state of 1950s Hollywood, that Gene Kelly’s performance goes beyond the conventional cinematic choreography. Embodying the spirit of cinematic innovation, from the early 1920s to the middle of the 20th century, the filmmakers turned what could’ve been a simple sequence on the street into a humorous and pure release of human expression.

As previously detailed, rudimentary sound recording technology was limited in the 1920s film industry and thus, such a complex musical number would have been entirely inconceivable. The 1950s, on the other hand, gave directors like Kelly and Donen access to a highly advanced technology palette that made it possible to create nuanced visual manipulation, authentic choreography, and thorough sound design. The rain itself is carefully manipulated and orchestrated in this scenario, acting as a co-performer alongside Lockwood. Every droplet is a carefully planned component of cinematic enchantment, as is its sound, rather than a natural phenomenon. As more than just movement, Kelly’s dance commemorates how humans have confounded technological constraints and celebrates how these new tools have effectively broadened the industry’s horizon of artistic potential. Each splash and pirouette in the water becomes a metaphorical representation of cinema’s technological liberation. The scene deconstructs the potential melancholy of technological transition by transforming it into a jubilant, almost childlike celebration of possibility. When Kelly splashes and dances, he’s not just playing in water--he’s symbolically playing with the product of the tools used to make this cinematic masterpiece.

In summary, Singin’ in the Rain is a highly complex work that examines the relationship between artistic reinvention, technological advancement, and cultural memory. It is far more than a sentimental trip through the golden age of Hollywood. Beneath its spectacular choreography and upbeat musical pieces, there is a nuanced commentary on the entertainment industry’s difficult metamorphosis, specifically within the dramatic transition from silent to sound movies. Through its careful use of mise-en-scène and comedic displays of acting, the film captures the hopes, concerns, and realization of goals within the industry as it grapples with technological advancement. The film’s capacity to simultaneously embrace and critique nostalgia, transforming the dramatic transition from silence to sound into an opportunity for artistic regeneration and creation, highlights its multi-layered approach to historical reflection. This paradox between celebration and self-aware irony is a powerful reflection of Hollywood’s character as a dynamic, self-mythologizing enterprise where innovation and progress are not only vital to its survival but also crucial for its progression.

Comments